The Math and the Graph Behind a Popular Match Game

Sr. Developer Advocate

9 min read

Overview

- The game and the math

- Graph-backed game you can play

- Graph as Judge pattern?

Most days, we use graphs to power serious systems. Fraud detection. Recommendations. Digital twins. Context for agentic AI.

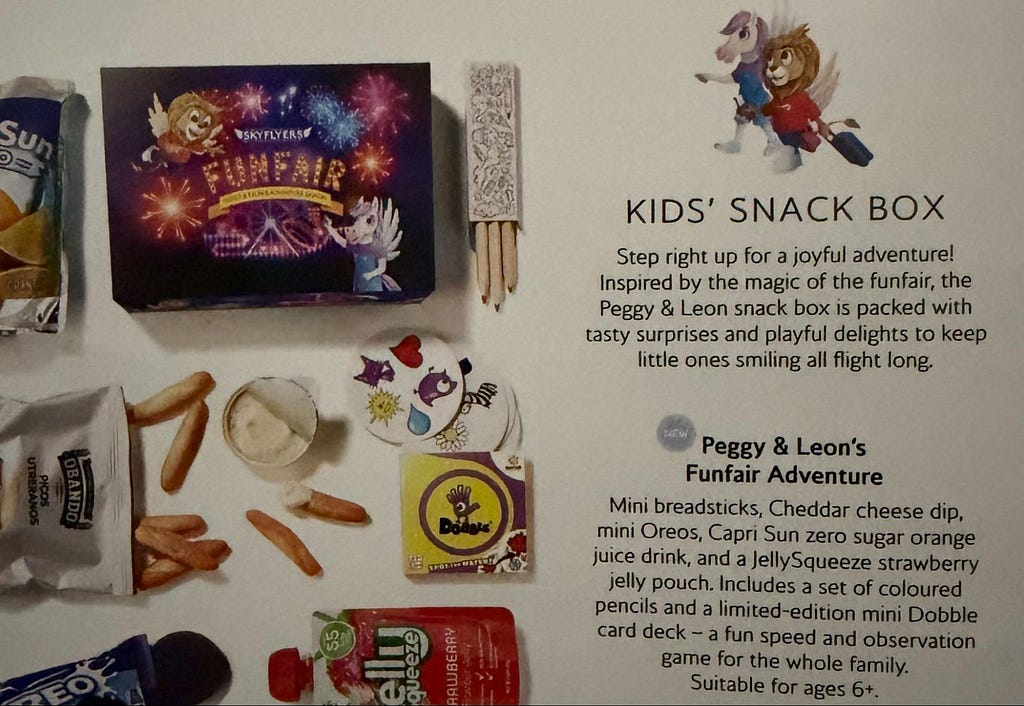

Today, we’re using graphs to help explain a children’s card game (that I love to play too!).

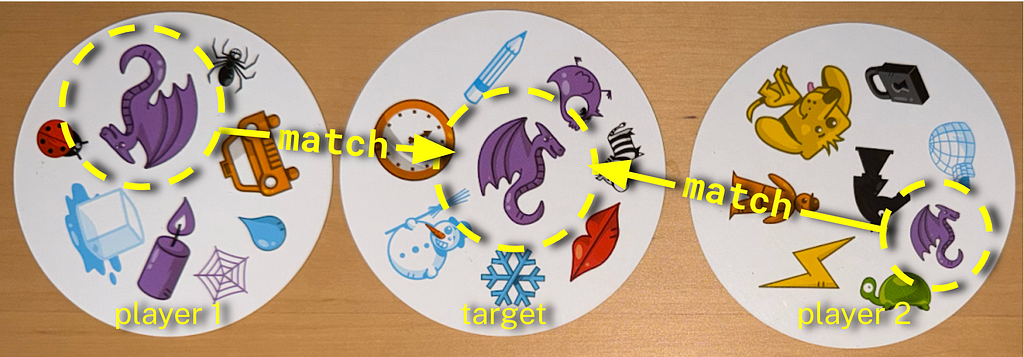

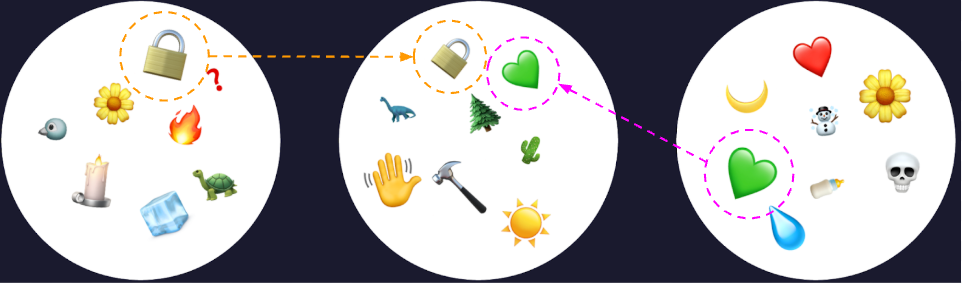

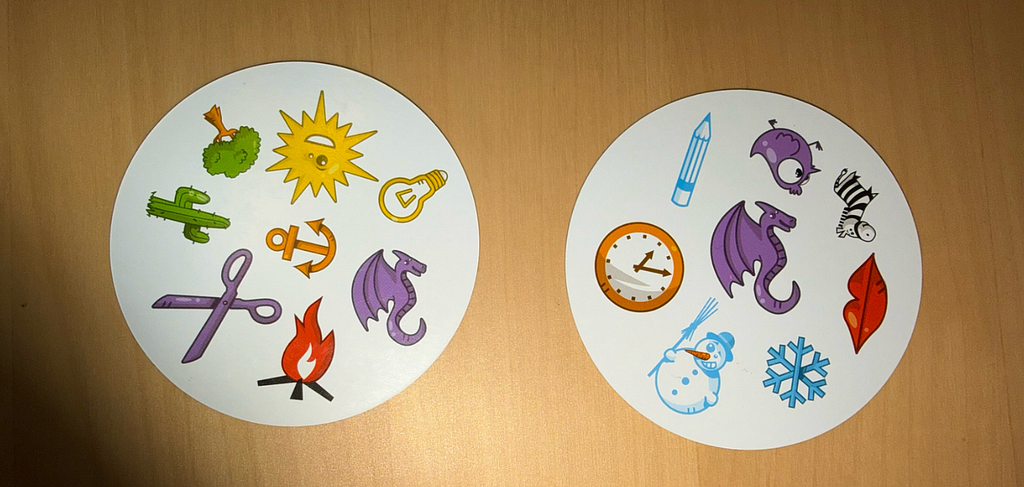

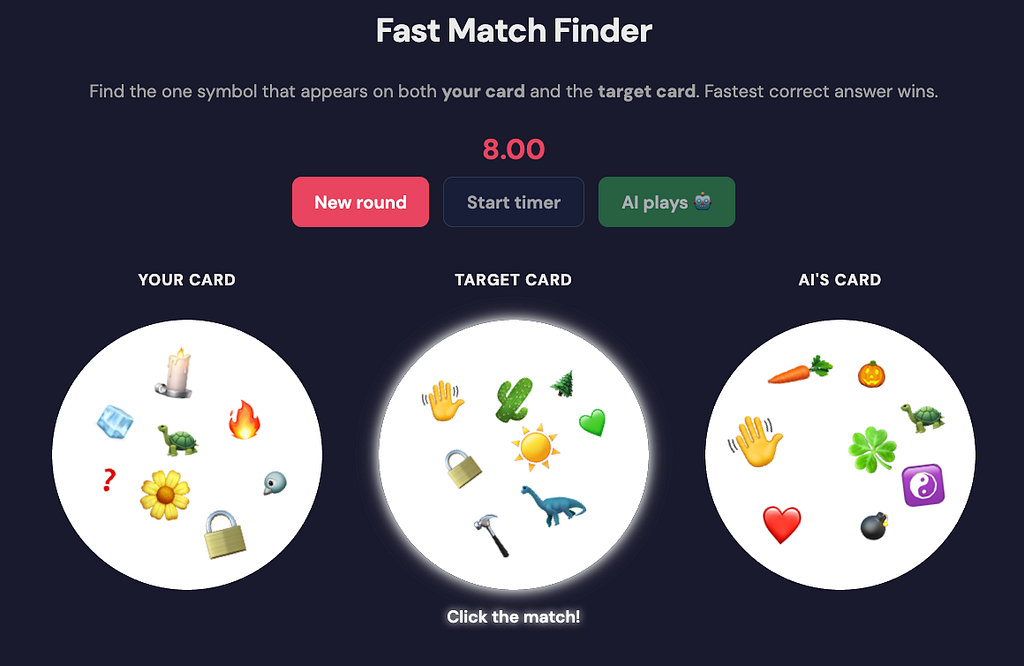

Spot It!® aka Dobble® looks deceptively simple. Every card has eight symbols. Between two cards, find the one symbol they share, shout it out first, grab the card, repeat.

That’s the whole game.

And yet there’s a constraint hiding in plain sight that makes this game’s deck far more structurally unforgiving than it looks:

- Every card has exactly 8 symbols.

- Any two cards share exactly one symbol (see cards above).

- Not zero. Not two. Exactly one.

If you’ve ever tried to design systems with such ironclad guarantees, your instincts are probably screaming, “Watch out! There’s definitely some math in there!”

A Deck That Shouldn’t Exist

The standard commercial deck has just 55 cards (a subset of the 57 in the full deck — see below).

And if you try to generate a deck like this naively, three things usually happen:

- You accidentally violate the “exactly one symbol matches” rule (easier if more “can” match).

- You end up needing thousands of cards (ensuring matches for everything).

- You cheat by putting the same symbol on everything (only one matching symbol).

None of those make for a good game (see Matt Parker’s video on Dobble for a great explanation of “bad” approaches and more).

So how did they do it?

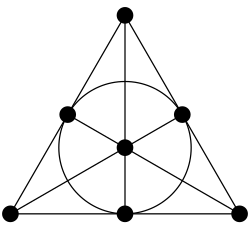

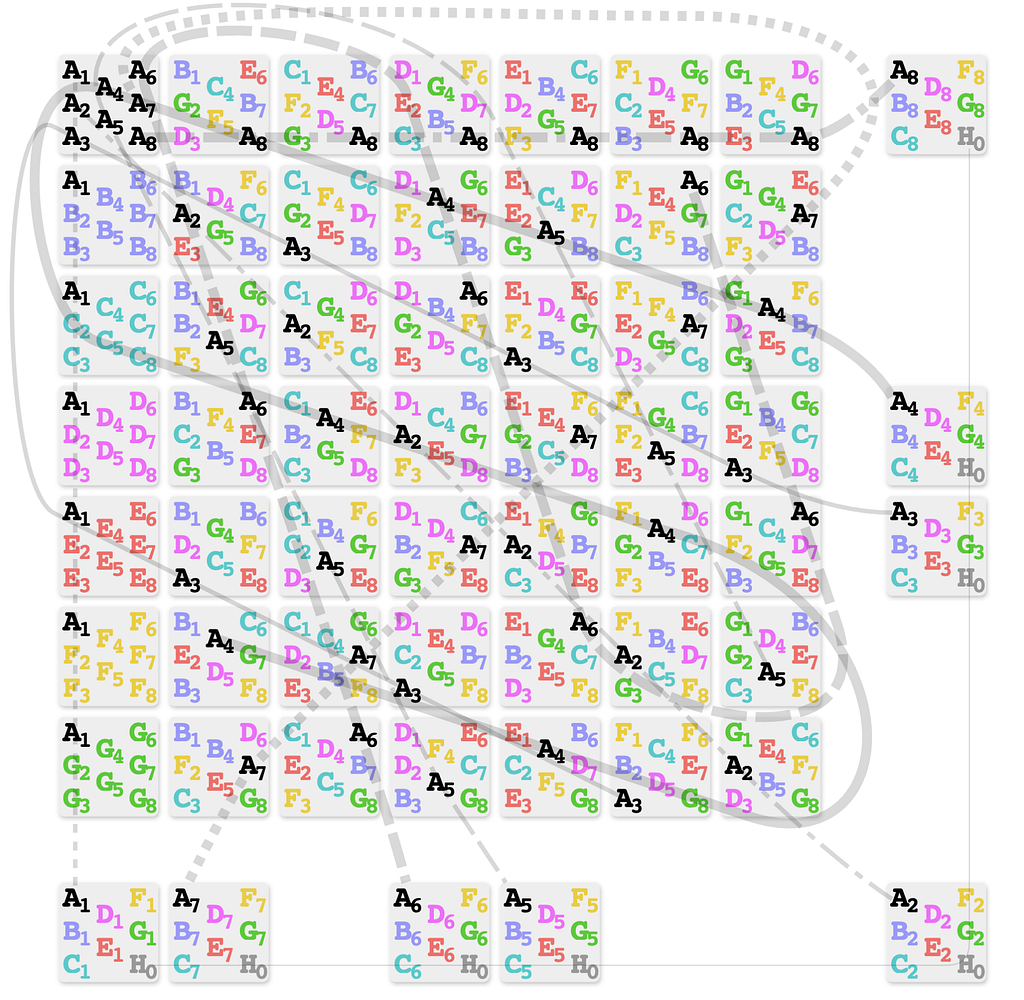

The answer is a beautiful mathematical object called a finite projective plane, specifically PG(2,7). Objects of this kind arise in projective geometry, where spaces are denoted PG(n, q) for various dimensions and orders. PG(2,7) is a two-dimensional projective plane of order 7 with a finite, discrete set of points and lines — though its point–line duality, and how it relates to ordinary affine geometry, can feel counterintuitive at first.

We’re going to map Dobble’s symbols & cards onto the points & lines of PG(2, 7).

The order can be used to calculate the particulars of a given deck/plane.

For a projective plane of order N:

- Symbols per card: N+1

- Cards in the deck: N²+N+1

- Each symbol appears on N+1 cards

- Any two cards still share exactly one symbol

The game rules stay the same — only the scale changes.

Finite projective planes exist whenever the order is a power of a prime, and it’s unknown if planes can exist for non-prime power orders. This mysterious object looks right at home in the graph world, so let’s play with it!

That’s all the math for today since we’re going to build the deck as a graph and explore it from the inside (if you want more right now, this video is what first got me hooked).

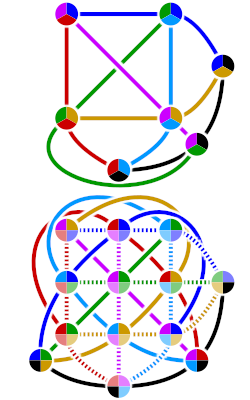

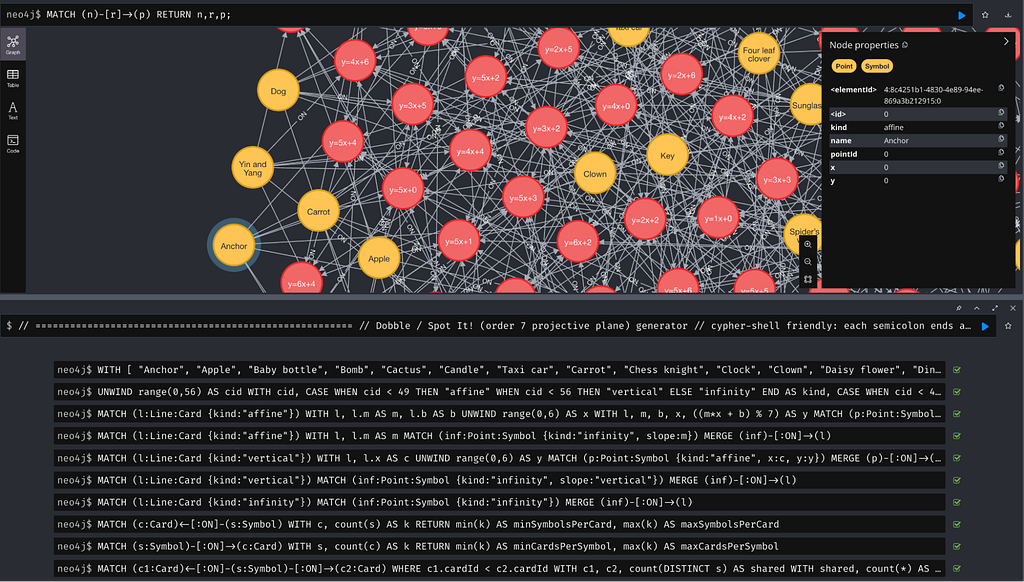

Building a Perfect Dobble Graph

Using Neo4j and Cypher, we can construct the full projective plane and use symbol names consistent with my physical Dobble deck:

Get the dobble.cypher script I used on GitHub.

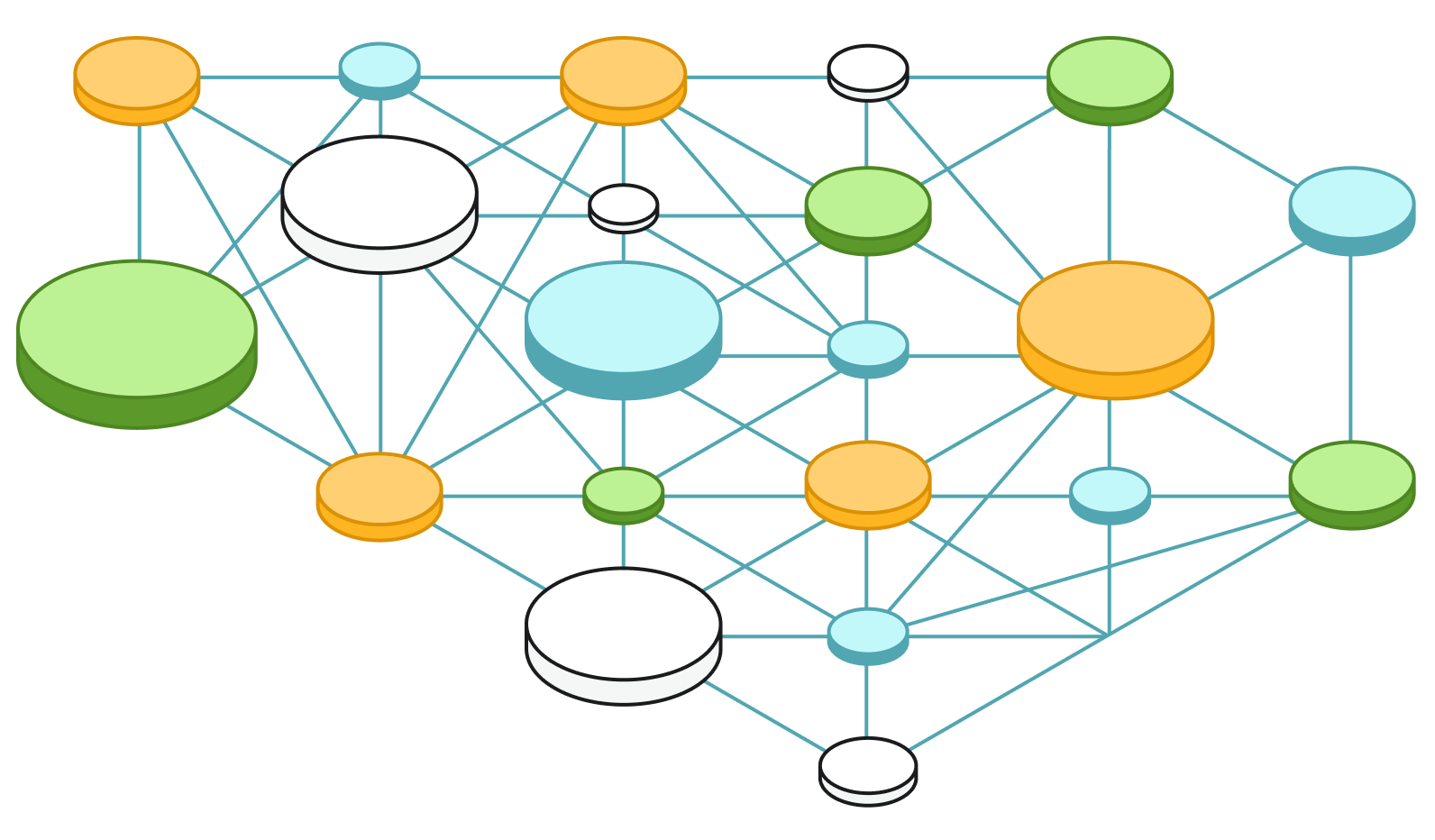

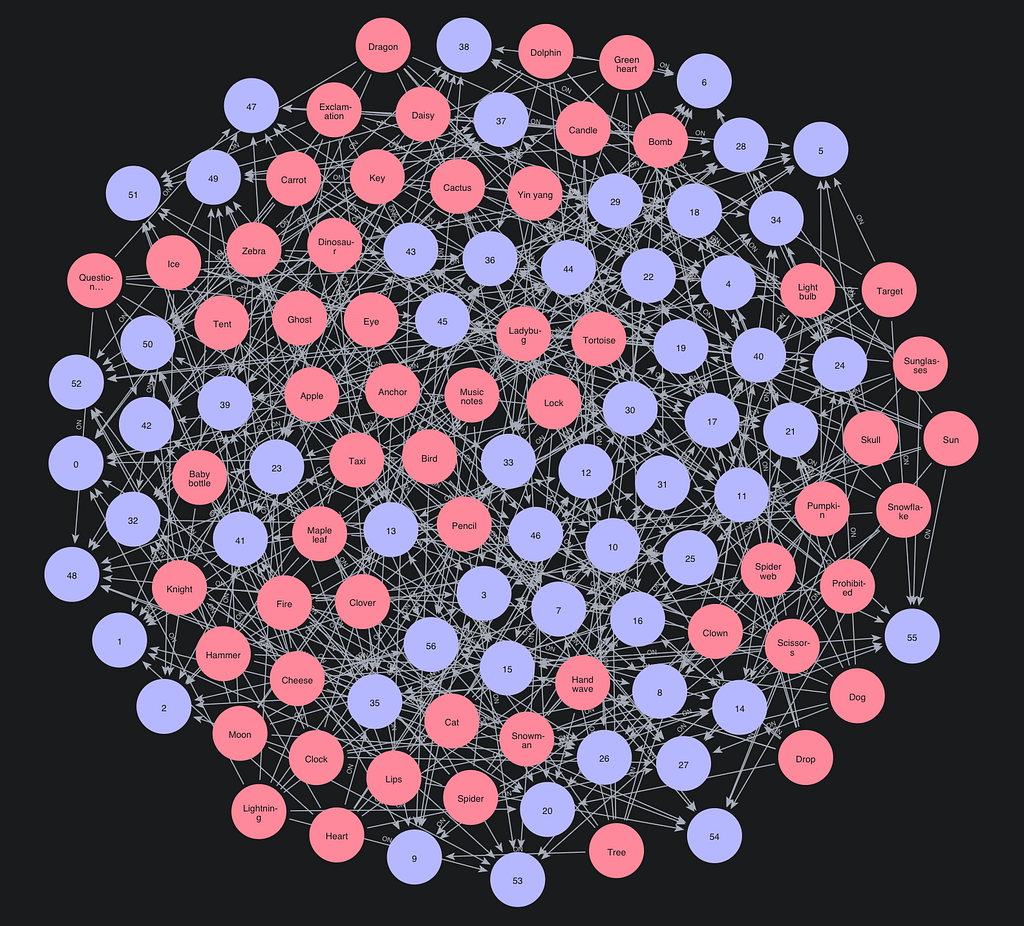

The model is almost embarrassingly simple:

- Symbol nodes (aka Point nodes, for an isomorphic math lens)

- Card nodes (aka Line nodes, also for math)

- An :ON relationship meaning “this symbol appears on this card”

That’s it.

The entire game reduces to one invariant:

Every pair of Card nodes has exactly one shared Symbol neighbor.

If that holds, the deck works. If it doesn’t, the game breaks.

The full Cypher script is long, but it does four things:

- Creates the 57 symbols

- Creates the 57 cards

- Connects them using projective geometry

a. Each card connected to exactly 8 symbols

b. Each symbol appearing on exactly 8 cards - Verifies all invariants

And because this is a graph, we can ask the game questions.

Let the Graph Play the Game

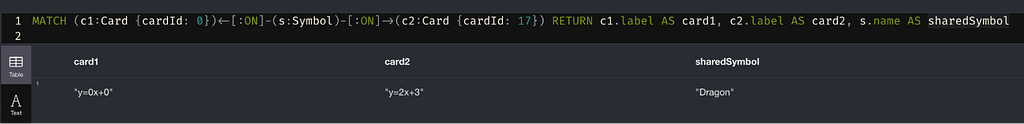

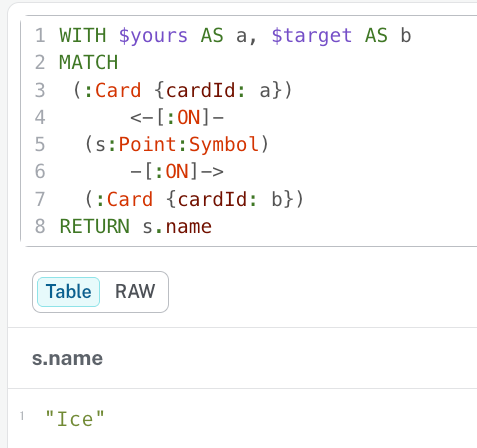

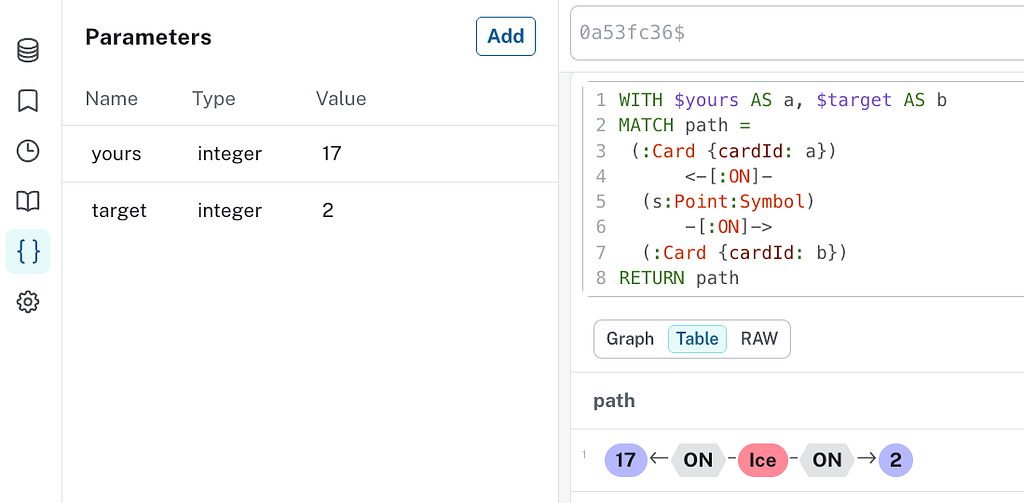

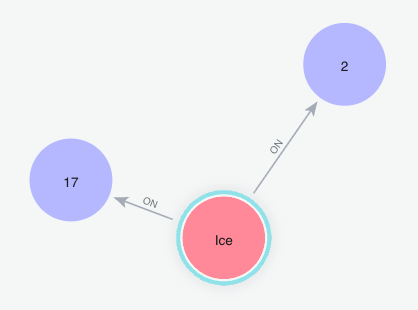

What symbol do cards 0 and 17 share?

MATCH (c1:Card {cardId: 0})<-[:ON]-(s:Symbol)-[:ON]->(c2:Card {cardId: 17})

RETURN c1.label AS card1, c2.label AS card2, s.name AS sharedSymbol;

That’s the game. No loops. No lookup tables. Just topology.

The False Twin Moment

At this point, I expected my graph deck to match my physical deck.

It didn’t. Not even close.

I don’t mean because there are only 55 cards in a commercial deck vs the 57 cards in a mathematically perfect deck. It was that the combinations of symbols on the cards didn’t line up. Same symbols. Same constraints. Different deck.

That’s when the next surprise landed.

5.6 Million Valid Decks

There is only one projective plane PG(2,7). But there are 5,667,648 distinct ways to assign symbols to cards while preserving all the rules.

Same math. Same guarantees. Millions of valid decks.

Dobble isn’t a deck.

It’s an equivalence class.

I’ll Make My Own!

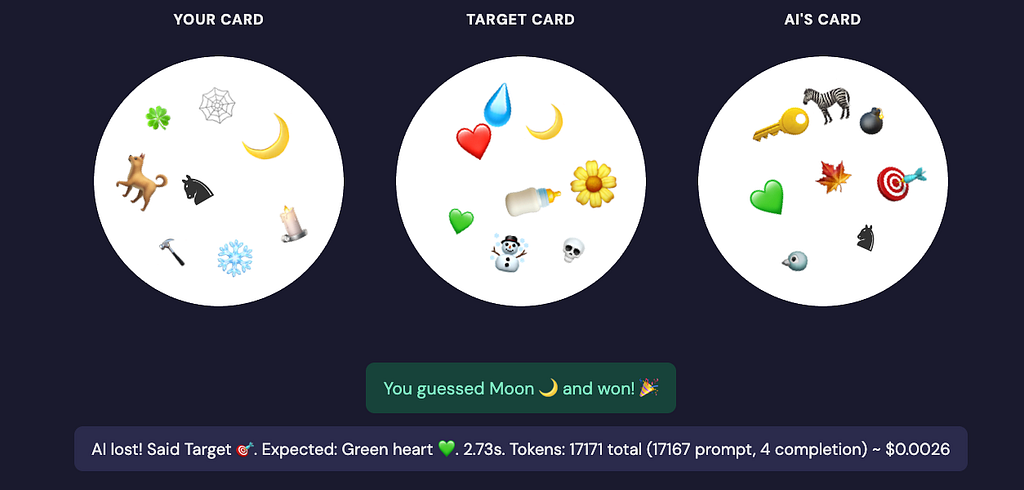

At this point, I though I would input all 57 of my cards into a graph so I would have an actual digital twin of my physical deck (might still do that), but I decided to try something else first — I vibe coded my own match game where I could test my speed or battle an AI model.

In this game, the referee isn’t an LLM as Judge, but rather a simple Graph as Judge.

GitHub – jpadams/fastmatchgame

Graph as Judge? Lean model?

Okay, I might be stretching things, but if you have a graph and queries that can deterministically provide the right answer every time, that’s a valuable model indeed. Plus the graph is a completely clear box, open to inspection and easy augmentation or enrichment.

Even if a black box, stochastic LLM knows about PG(2, 7), it can’t answer questions about your particular instance without a lot of tokens or retraining, and even then, it might well get it wrong for reasons that aren’t clear.

The graph, on the other hand, will never be wrong. It can’t be. Every question and answer possible is already materialized. Answers are generated by speedily following graph edges like pointers instead of “magical” transformer processes requiring a GPU. A well-specified query filters down to the inevitable truth — in this case, that any two cards have exactly one shared symbol.

That kind of guarantee makes the graph a perfectly fair and all-knowing judge. In my version of the game, when an LLM or a human generates an assertion as to which symbol matches, the graph is consulted and makes its ruling.

While not everyone needs a simple static model like PG(2, 7) as a graph, many of the most valuable systems ever built for web search, drug discovery, product recommendations, and networks have been graphs — often very large, dynamic, evolving graphs — that employ similar queries and specialized graph algorithms to answer difficult, timely questions. Additionally, right now everyone is talking about context graphs and graph memory as new fundamental building blocks of agentic applications.

What all these graphs have in common is an extensible, reliable structure that can answer the “what” and the “why”.

And of course, graphs can give us insight into the math that make simple games like Dobble such elegant fun.

What next?

To dig in deeper, fire up a Neo4j graph database and try out one of these challenges, including building a new Neo4j Aura Agent.

- Run the Fast Match Finder game with Neo4j. The app will auto-populate the database with the graph!

a. Double-click the game outputs to reveal the hidden Cypher query that decides the game.

c. Try more queries in the Neo4j query interface to explore the graph/game/PG(2, 7). - Play with and extend my original Dobble graph script.

a. Load it up into a fresh Neo4j instance.

b. Use images of cards to produce a true digital twin of your favorite deck.

c. Figure out which 2 cards are missing from your commercial deck (55 vs 57). - Once you have a Dobble graph in Neo4j that you’re happy with, build a Neo4j Aura Agent on top. Your agent could use Cypher tools like:

a. Show cards by id (1–57) and display their symbols

b. Show all cards which share a certain symbol

c. Get the matching symbol between two cards (the query used to judge the games)

d. Serve your agent as an HTTP MCP server to power another agent!

e. Whatever you can dream up! 🦄 🌈

The Math and the Graph Behind a Popular Match Game was originally published in Neo4j Developer Blog on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Dobble® and Spot It!® are registered trademarks of their respective owners. This article is not affiliated with, endorsed by, or sponsored by the trademark holders.